|

|

VII.C.1. (IV.C.4.) (XIII.C.4.) (III.B.3.d.) |

Vibrational scaling factors

The vibrational frequencies produced by ab initio programs are often

multiplied by a scale factor (in the range of 0.8 to 1.0) to better match

experimental vibrational frequencies. This scaling compensates for two problems:

1) The electronic structure calculation is approximate.

Usually less than a relativistic full configuration interaction is performed.

2) The potential energy surface is not harmonic.

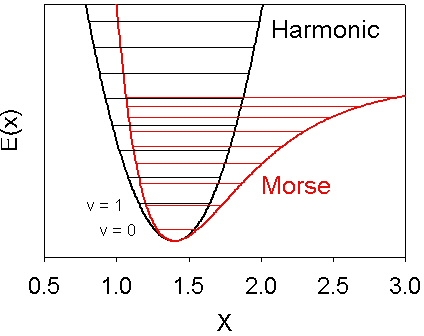

For bond stretches a better description of the potential energy surface

is given by the Morse potential

E(x) = D(1-exp(-β( x-x0 )))2

illustrated below.

In this equation E is the potential energy,

D, β, and x0 are constants,

and x is the interatomic distance.

The programs that predict vibrational frequencies do so by calculating

the second derivative of the potential energy surface with respect to the atomic

coordinates. This provides the curvature at the bottom (minimum) of the well.

For a harmonic potential E(x) = k x 2 this is directly related to the vibrational

energy level spacing. For a Morse potential (with the same second derivative at

the minimum) the anharmonicity causes the vibrational energy levels to be more

closely spaced as illustrated in the figure.

Experimentally usually the fundamental (v=0 to v=1 energy) is measured. If enough vibrational levels are observed a harmonic frequency can be estimated with a formula such as G(v) = ωe(v+1/2) - ωexe(v+1/2)2 + ωeye(v+1/2)3 + ... where G(v) is the vibrational energy, v is the vibrational quantum number, ωe is the harmonic frequency, and ωexe and ωeye are anharmonic constants. For polyatomic molecules usually only the fundamental is experimentally observed.

How we calculate the vibrational scaling factors

We use the experimentally observed vibrational frequencies (νi), and the theoretical vibrational frequencies (ωi).The scaling factor (c) and its relative uncertainty (ur) are obtained from the following sums over the vibrational frequencies:

c = Σ(νi •

ωi)/

Σ(ωi2)

ur2 = (Σ(ωi2

• (c-νi/ωi)2))/(Σ(ωi2))

Try out the CCCBDB pages for calculating vibrational scaling factors.

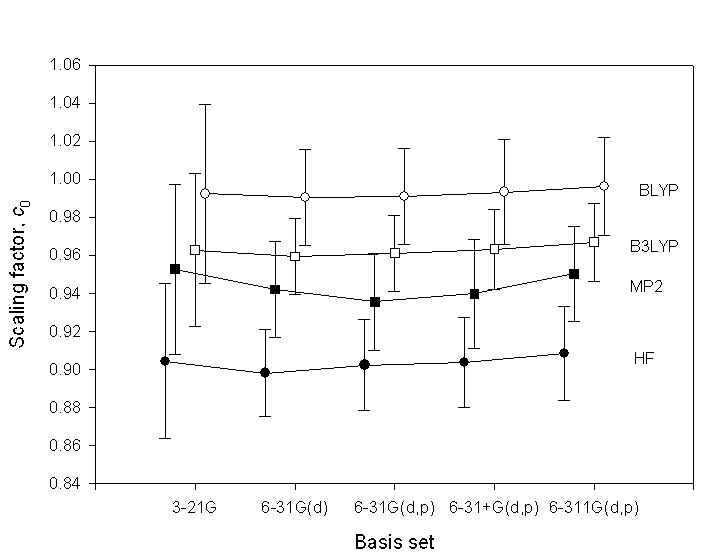

How much do the factors change with basis set?

The following figure shows several scaling factors and their uncertainties. The figure is from: K. K. Irikura, R. D. Johnson III, R. N. Kacker, J. Phys. Chem. A., 2005, 109(37), 8430-8437.Filled cirlces = HF, filled squares = MP2, open cirlces = BLYP, open squares = B3LYP.

The scaling factors depend weakly on basis set. The uncertainties are about twice as large for the 3-21G basis set as for the other basis sets, all of which include polarization functions. This suggests that polarization functions are important for avoiding markedly poor predictions of vibrational frequencies. For larger basis sets the scaling factors and uncertainties have non-significant changes. Thus the same scaling factors can be used for other basis sets.

See the pages listing vibrational scaling factors: III.B.3.a Precomputed vibrational scaling factors.